Two days ago, one of our students email me the following post. It is so compelling that we’ve decided to post a second post on the same day. She says it’s not a poem, but it is deeply powerful and we are honored to post it.

john sj

p.s. It happens that Tom Florek, whose picture is in this post and is referred to by the student, is in our Jesuit house today and that fills me with joy.

*****************

Service trip student reflection

Good afternoon,

I have read many of your poetry communications and some have covered the topics of empathy and immigration. Perhaps you can share my reflection in your poetry emails, although it’s not poetry. I want to share what I saw and remind us all of the importance of being active members of a loving and global human family.

Vania Noguez

IMMIGRATION, VOICES FOR JUSTICE

“FAITH IS ALL THEY HAVE LEFT”: ENCOUNTER ON THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDER

BY VANIA NOGUEZ | May 9, 2019

When I heard this provocative statement from Rafael Garcia, S.J., a Jesuit with the Encuentro Project, an immersion program on the U.S.-Mexico border region in El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, during an orientation reflection, I was immediately confused, yet intrigued. Little did I know, these words would be one of many life-changing realizations during my experience, aiding my understanding of the faith and suffering of asylum seekers and refugees. My personal encounter with such a discomforting reality helped me to better understand what most never will.

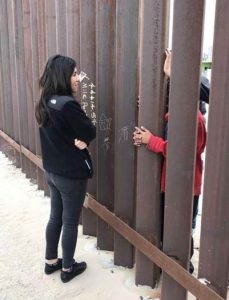

Vania Noguez speaking with residents of Ciudad Juarez through the U.S.-Mexico border wall.

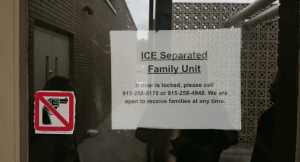

The Encuentro Project facilitates learning about the current immigration crisis through meetings with lawyers, community activists, spiritual leaders, Border Patrol, and visits to a refugee shelter and ICE detention center. This specific location has been in the media spotlight as the epicenter of the U.S. refugee crisis. A few days before we arrived, a 7-year-old girl from Guatemala died in Border Patrol custody in El Paso.

As a 21-year-old Hispanic-American from the Michigan suburbs, I experienced a reality check of privilege in college when I met other Hispanics my age who were impacted by current immigration policies. With this, I realized my own ignorance of these issues because they had never impacted me personally. I knew I wanted to see the truth at the border with my own eyes, explore my social role as a Hispanic-American woman, and bring back knowledge to promulgate change.

My first encounter began when a bus arrived at the shelter where we were volunteering. It was carrying nearly 100 refugees, mostly from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. They had just been released from ICE detention. As they stepped out of the bus to enter the safety of the shelter, we welcomed them with smiles and “bienvenidos” (welcome) but this became increasingly difficult as we saw women, children, and men carrying looks of fear and limping from exhaustion. Few carried personal items in flimsy garbage bags and most arrived with no belongings at all. There were young and old women carrying toddlers in their arms with a strength I could not comprehend.

As I went back and forth from the clinic and cafeteria translating, one woman called for me and asked me if I could spare a sanitary pad. I realized she was sitting on the edge of her seat while holding her young son. She explained that she was denied feminine hygiene products in detention and had bled into her pants. They were dried stiff with blood. I immediately ran to the resource room to find sanitary pads, wrapped them in a bag, and delivered them to her discreetly. I told her I would help her to find a change of pants as soon as possible but the available donated pants were all too big. During this encounter, I felt weak with anger as I realized this mother had been reduced to a level that was beyond inhumane. She was embarrassed and her dignity as a woman had been degraded. I asked her how old she was and she said she was 23, which is only 2 years older than me. Around us, there were mothers breastfeeding their babies with no privacy and I felt a strong presence of motherhood, extreme endurance, and sacrifice.

My most powerful encounter was at the women’s mass during our visit to an ICE detention center. I held a microphone and greeted over a hundred women in orange jumpsuits. I was taken aback at their strong response, “buenas tardes” (good morning), all in unison. They all wanted their voices heard. Fr. Tom Florek, S.J., a Jesuit in residence at the University of Detroit Mercy focused on Hispanic/Latino Formation Development who was a member of our delegation, and Fr. Garcia told the nativity story of Mary and Joseph. Fr. Garcia mentioned that the story had many connections to the women. Mary, who traveled on the back of a donkey, pregnant, about to give birth, feared the future. She ended up giving birth to Jesus in a humble stable. The pregnant women who arrived at the shelter similarly faced the possibility of giving birth in a detention center, on a bus, in the desert, or in imminent danger. This made me reflect on the courage and strength of Mary, which was reflected in the hundred women listening to the mass, many of whom had been separated from their families and children.

During the sermon, one woman suddenly collapsed and had an apparent seizure. The women closest to her held her as she fell to the ground and helped prevent her from hitting her head. After paramedics took her away, another woman standing in the front row began to sway. She began to sob loudly and I noticed her legs were trembling. We had been given instructions to not engage in any physical touch, but I went to her and kneeled next to her squeezing her hand in support as the sermon continued. This was a reciprocal moment. We were two women, strangers who looked alike, close in age, holding each other, unified in our hearts, crying mutually during Christmas mass. This was the crescendo of compassion. When I kneeled with this woman, we connected in faith, journey, understanding, and solidarity.

The women held each other up as a loving community and together they shared an interconnected sorrow. As I looked around, I felt the spirit of encounter in this unsettling experience and began to encounter myself through others and through their faith. This was the first time in my life that I experienced faith in its rawest form. I saw people hardly able to stand on their own feet from the emotions, crying for their children, profusely praying “ten piedad” (have mercy). This moment transcended all the division I had felt and I realized I was amongst living members of the nativity story, the story of Mary and Joseph. They were fleeing from violence, poverty, and persecution, but were faced with rejection at every door they knocked upon along their journey. The refugees I met fled to America for safety but were met with rejection again and again, along with imprisonment.

After mass, some women approached me, kissed me on the cheek, and told me I reminded them of their daughters. One woman told us to pray for her because her five children had been murdered in Honduras. An older woman came up to me and whispered in my ear asking if I could help her. She showed me a crumpled document with handwritten scribbles in English that I could barely understand. She asked me what the scribbles meant. I told her I wasn’t sure but that it seemed to say that something was pending, maybe a court date. They were captive without explanation, didn’t know what time of day it was, and were negated explanation of their legal rights and process.

Bishop Mark Seitz from the Diocese of El Paso with University of Detroit Mercy Encuentro Project participants.

These transformative encounters with a refugee population made me realize that I couldn’t understand the immigration crisis by just looking at the news and reading headlines. However, I only encountered small amounts of the truth, as all of us do. In order to better understand the wrongs against humanity, we need to reverse the tables and ask ourselves how we would want to be treated. Catholic Social Teaching explains that we have a universal responsibility as Catholics and as human beings to embrace and support suffering communities. By learning about people who suffer differently than ourselves, through interaction with diverse cultures, we can connect as a holy human family and truly be moved to action.

Vania Noguez is a student at the University of Detroit Mercy.