Mary Oliver: “there was a new voice which you slowly recognized as your own”

“One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting their bad advice”

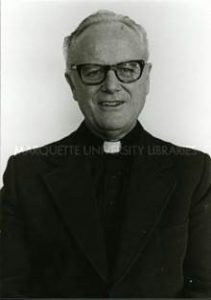

Late during the Lenten season of 1965, the small group of “Province Consultors” met with Pedro Arrupe, (newly named the Superior General of the world wide Jesuit Order) in an O’Hare hotel meeting space to address a crisis. The current mid-west Provincial’s ham-handed manner threatened to drive much of the younger half of the Province out, enough that a startling number of influential Jesuits wrote to Rome warning that decisive action was needed immediately. It happened that Arrupe was making his first visit to the U.S. as Superior General. The small group met all day. Arrupe asked the consultors whether the situation was as dire as the 50 + letters said. The consulters said “yes.” Then, Arrupe asked who in the province might the younger men trust. A consensus told him “Joe Sheehan, the current Novice Director.” That same day Arrupe fired the provincial and named Joe, to be announced two weeks later, on Easter.

On Pine Ridge we young Jesuits were 5; when we read the letter Easter morning, we began dancing around the dining room, laughing with wonder and joy (e.g., one of us wandered around the room in a daze saying “There is a God; I believe it now, there is a GOD!”)

Hindsight says that Joe paid a high price to meet the crisis; he began to call Jesuits young and old to face the province’s pervasive but little-recognized racism that had created a cultural assumption that the Rez was a penal colony for outcast Jesuits who had gotten themselves in trouble or who were perceived to be third string minds. After his tumultuous 6 year term and many battles, Joe took a sabbatical and then asked to return to the Rez, for the rest of his life it turned out. His hospitality to Lakota men and women and children became legendary. When he died (cancer, I think), he was buried in the cemetery of Manderson village. During my sabbatical month there in September, my soul friend Mary Tobacco and I drove the c. 40 miles to visit not only Joe’s grave, but also Mary’s legendary ancestor Standing Bear and Black Elk, life-long close friends. Black Elk became world famous as a wicasa wakan who John Neihardt interviewed over a long time and published the still-contemporary book Black Elk Speaks. In recent decades, anthropologist Michael Steltenkamp, sj published a second account, this time by Lucy Black Elk, about her grandfather, Black Elk, who also served as Catholic pastor in Manderson District for c. 40 years. While Mary and I stood still there for a while, a meadowlark began to sing, somewhere close to Joe’s grave: “Maybe that’s Fr. Sheehan welcoming us,” said Mary.

I love the accident of this early November calendar reminding me of how much I and very many other people owe to Joe’s understated courage and his revolutionary recognition that the racist wounds on Pine Ridge called for a conversion into deep cross-cultural mutual hospitality – standing in that cemetery, near a caucasian priest, a Lakota holy man, and a war leader listening to the meadowlark as a sacred voice telling us that we were all welcome there that morning.

John G. Neihardt (from left), Nicholas Black Elk and Standing Bear of the Oglala Sioux

meet during an interview session for “Black Elk Speaks” in Manderson, S.D., in May 1933.

(Photo by Enid Neihardt; Courtesy of The Neihardt Trust)

Joe Sheehan, sj

Died November 4, 1997

Best to read Mary Oliver out loud, with pauses. She makes good company for troubled times like the present and would not be surprised by this remembrance of Joe Sheehan, sj, Black Elk, and Standing Bear and the prairie Manderson cemetery where their bodies have come to rest near one another.

Monday afternoon, alive with crisp autumn air. Have a blest day.

john sj

Today’s Post “The Journey”

One day you finally knew

what you had to do, and began,

though the voices around you

kept shouting

their bad advice —

though the whole house

began to tremble

and you felt the old tug

at your ankles.

“Mend my life!”

each voice cried.

But you didn’t stop.

You knew what you had to do,

though the wind pried

with its stiff fingers

at the very foundations,

though their melancholy

was terrible.

It was already late

enough, and a wild night,

and the road full of fallen

branches and stones.

But little by little,

as you left their voice behind,

the stars began to burn

through the sheets of clouds,

and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could do —

determined to save

the only life that you could save.

Mary Oliver

September 10, 1935